Pancreatitis Risk Calculator for DPP-4 Inhibitors

This calculator helps you understand your personal risk of developing acute pancreatitis while taking DPP-4 inhibitors. Based on data from over 47,000 patients in clinical studies, this tool shows how your medical history affects your risk.

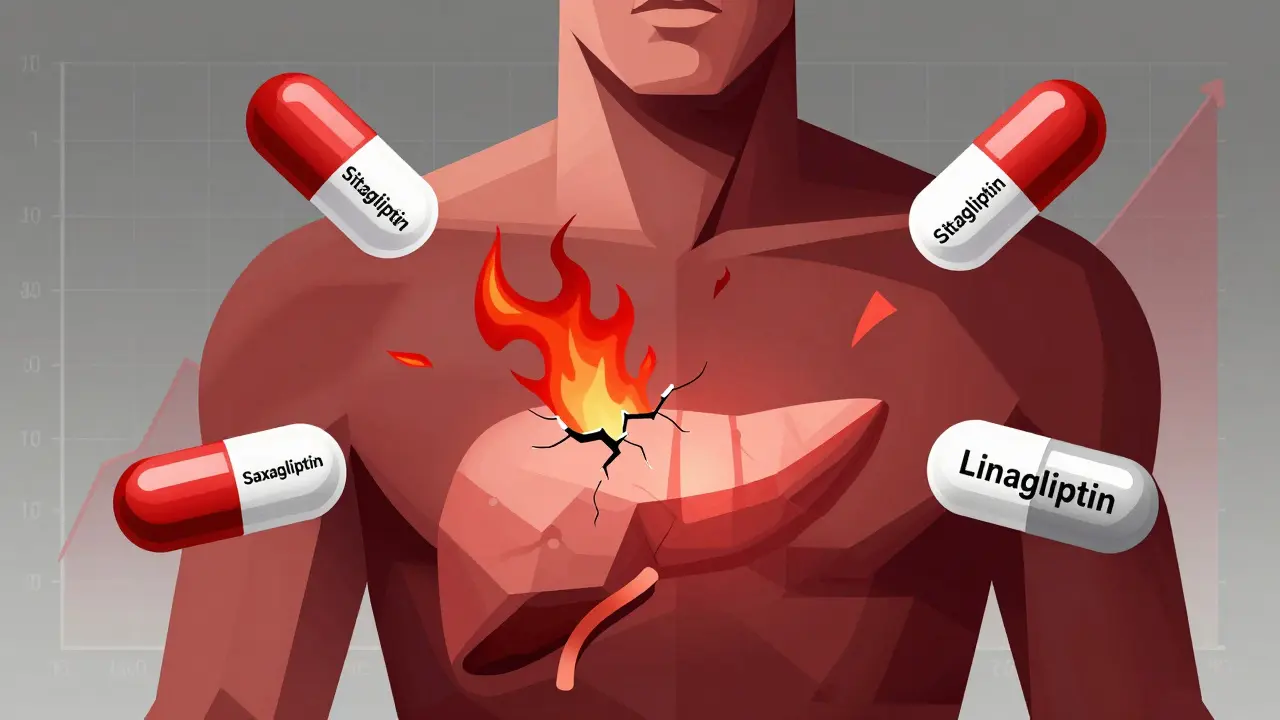

When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing crashes or weight gain is a win. That’s why DPP-4 inhibitors - also called gliptins - became so popular. Drugs like sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza), and linagliptin (Tradjenta) are taken daily, don’t cause low blood sugar on their own, and don’t make you gain weight. But behind the convenience lies a quiet, serious risk: acute pancreatitis. It’s rare, but it’s real. And if you’re taking one of these drugs, you need to know the signs.

What Are DPP-4 Inhibitors?

DPP-4 inhibitors work by blocking an enzyme that breaks down incretin hormones. These hormones help your body release more insulin after meals and reduce the amount of sugar your liver pumps out. The result? Better blood sugar control without the usual side effects of older diabetes meds.

The first one, sitagliptin, got FDA approval in 2006. Since then, four others joined the list: saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin, and vildagliptin (not available in the U.S.). Together, they make up about 15% of all oral diabetes prescriptions in the U.S., according to 2022 data. They’re often used when metformin isn’t enough, or when patients can’t tolerate other drugs.

Pancreatitis: The Hidden Risk

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas - a vital organ that makes insulin and digestive enzymes. Acute pancreatitis hits fast: severe, constant pain in the upper belly, often radiating to the back. Nausea, vomiting, and fever can follow. It’s not just uncomfortable - it can be life-threatening.

Early clinical trials didn’t catch much. Too few cases happened during the short study periods. But once these drugs hit the real world, reports started piling up. The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) flagged the issue in 2012. The FDA followed with safety updates. By 2019, a major meta-analysis of over 47,000 patients confirmed: DPP-4 inhibitors raise the risk of acute pancreatitis by 75% compared to placebo.

Here’s what that means in real numbers: for every 1,000 people taking a DPP-4 inhibitor for two years, you might see one to two extra cases of pancreatitis. That’s about one extra case every 834 patients over 2.4 years. Sounds low? It is. But when it happens, it’s serious.

How Do We Know It’s the Drug and Not Diabetes?

People with type 2 diabetes already have a higher baseline risk of pancreatitis - from obesity, high triglycerides, or gallstones. So how do we know it’s the drug, not the disease?

Studies compare patients on DPP-4 inhibitors to those on other diabetes drugs or placebo. Even after adjusting for known risk factors, the extra risk sticks. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology found a reporting odds ratio (ROR) of 13.2 for DPP-4 inhibitors - meaning pancreatitis cases were over 13 times more likely to be reported with these drugs than with others in global safety databases.

And it’s not just one drug. All approved DPP-4 inhibitors show the same signal. Even linagliptin, which had fewer cases in trials, showed a 79% relative increase in pancreatitis incidence in a 2021 meta-analysis.

How Does It Happen? The Mystery

No one knows for sure. Animal studies haven’t given a clear answer. Some theories suggest the drugs might cause abnormal enzyme buildup in the pancreas or trigger immune reactions. But none of these have been proven. The mechanism remains unclear - which makes it harder to predict who’s at risk.

What we do know: if you stop the drug, the pancreatitis usually goes away. The MHRA found that in most cases, symptoms improved after discontinuation. But 17.7% of reported cases were serious - requiring hospitalization or leading to complications.

How Do DPP-4 Inhibitors Compare to Other Diabetes Drugs?

It’s useful to see how DPP-4 inhibitors stack up against other options.

- SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin, dapagliflozin): These have a significantly lower pancreatitis risk than DPP-4 inhibitors. Plus, they help with heart and kidney protection - which is why they’re rising in popularity.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists (like liraglutide, semaglutide): These also carry a pancreatitis risk, but lower than DPP-4 inhibitors. Their ROR is about 9.65, compared to 13.2 for gliptins. Still, they’re often preferred now because of their weight-loss and cardiovascular benefits.

- Metformin: The first-line drug. No pancreatitis risk. Low cost. Side effects are mostly stomach upset - which often fades.

- Sulfonylureas (like glimepiride): Can cause low blood sugar and weight gain. No strong link to pancreatitis.

So while DPP-4 inhibitors are safer than some older drugs, they’re no longer the top choice for many doctors - especially when newer options offer more benefits with fewer risks.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on a DPP-4 inhibitor will get pancreatitis. But some people are more vulnerable:

- Those with a history of pancreatitis

- People with gallstones or high triglycerides

- Heavy alcohol users

- Those with obesity or metabolic syndrome

If you have any of these, your doctor should think twice before prescribing a DPP-4 inhibitor. The American Diabetes Association still lists them as an option - but with clear warnings.

What Should You Do If You’re Taking One?

You don’t need to stop your medication on your own. But you do need to be alert.

Before starting: Ask your doctor to explain the signs of pancreatitis. Write them down.

While taking it: Watch for:

- Severe, constant abdominal pain - especially if it radiates to your back

- Nausea or vomiting that doesn’t go away

- Fever or rapid heartbeat

If you feel any of these, call your doctor immediately. Don’t wait. Get your pancreatic enzymes checked (amylase and lipase) and possibly an ultrasound to rule out gallstones. Your doctor should stop the DPP-4 inhibitor right away if pancreatitis is suspected.

And if you’re diagnosed - report it. Use the FDA’s MedWatch system or your country’s adverse event reporting program. These reports help regulators track risks and protect others.

Are DPP-4 Inhibitors Still Used?

Yes. Despite the risk, they’re still prescribed. Why? Because for many people, the benefits still outweigh the risks.

They’re weight-neutral. They rarely cause low blood sugar. They’re easy to take - one pill a day. And unlike some older diabetes drugs, they don’t raise heart attack risk. In fact, large trials for sitagliptin, saxagliptin, and alogliptin showed they’re safe for the heart.

Global sales hit $5.8 billion in 2022. Sitagliptin remains the most prescribed in the U.S. But prescriptions are slowly shifting. More doctors are starting patients on SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists - especially if they have heart disease, kidney issues, or obesity.

For someone without those conditions, with no history of pancreatitis, and who needs a simple, low-risk pill - DPP-4 inhibitors still have a place.

What’s Next?

Researchers are now looking for genetic markers that might predict who’s more likely to develop pancreatitis on these drugs. If found, we could one day test patients before prescribing - making treatment safer and more personal.

Real-world data from 1.2 million patients in 2023 confirmed the risk is still there - but low. The absolute increase in risk? Just 0.14% higher than other diabetes drugs. That’s why regulators haven’t pulled these drugs off the market. But they’ve made the warnings louder.

Drug safety systems like the FDA’s Sentinel Initiative and the WHO’s global database keep watching. So far, the signal hasn’t faded.

Bottom Line

DPP-4 inhibitors are not dangerous for most people. But they’re not risk-free. The chance of pancreatitis is small - but when it happens, it’s serious. If you’re on one, know the symptoms. Talk to your doctor about your personal risk. And if you feel sudden, severe belly pain - don’t ignore it. Your pancreas can’t wait.

Mussin Machhour

December 26, 2025 AT 03:43Been on Januvia for 3 years and zero issues, but I get it - if your belly starts screaming like you swallowed a live hornet, don’t wait to call your doc. I’d rather be safe than sorry.

Carlos Narvaez

December 27, 2025 AT 02:47Let’s be honest - if you’re taking a gliptin, you’re probably not optimizing your lifestyle. Metformin’s been the gold standard for decades. Why are we still entertaining these overpriced, overhyped pharma toys?

Harbans Singh

December 27, 2025 AT 07:40I’m from India, and here we see a lot of type 2 diabetes cases without access to fancy meds. Still, I’ve seen patients on sitagliptin who developed pancreatitis after months - and yes, it resolved after stopping. The key is awareness. Not fear. Awareness.

Winni Victor

December 28, 2025 AT 03:55Oh great. Another drug that ‘doesn’t cause weight gain’ - right up until your pancreas turns into a sack of angry bees. Big Pharma’s got us on a treadmill of ‘safe’ side effects that just happen to be fatal. I’m not taking my pills tomorrow. Let the FDA explain why my stomach hurts.

sagar patel

December 29, 2025 AT 08:0275% increased risk is meaningless without absolute numbers. 0.14% higher than placebo. That’s 1 in 700. You’re more likely to die from stepping on a LEGO.

Christopher King

December 29, 2025 AT 21:16They’ve been hiding this since 2006. The FDA approved it because the CEO of Merck donated to the senator’s campaign. The ‘meta-analysis’? Funded by SGLT2 manufacturers. I’ve got a cousin who died after taking Januvia - they called it ‘idiopathic pancreatitis.’ Bullshit. It was the drug. They know. They all know.

They’re not pulling it because Big Pharma controls the narrative. The same way they controlled the opioid crisis. Same playbook. Wake up.

Oluwatosin Ayodele

December 30, 2025 AT 10:07People in Nigeria get diabetes from eating too much white rice and sugar syrup. They can’t afford these pills. If they did, they’d be grateful. Your first-world panic about a 0.14% risk is embarrassing. Focus on eating less sugar before you blame the medicine.

Jason Jasper

January 1, 2026 AT 02:44I’ve been on linagliptin for two years. No symptoms. But I’ve told my doctor I’ll stop immediately if I get any unexplained belly pain. It’s not about fear - it’s about responsibility. I read the studies. I know the signs. That’s all I can do.

Justin James

January 1, 2026 AT 17:48Think about it - if the pancreas is inflamed, and DPP-4 inhibitors increase incretin activity, which stimulates pancreatic enzyme secretion, isn’t it possible that prolonged enzyme overload causes micro-trauma? We’ve seen this in animal models with prolonged GLP-1 exposure. And guess what? DPP-4 inhibitors prolong GLP-1 too. So it’s not just correlation - it’s mechanistic plausibility. The fact that the mechanism isn’t fully mapped doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. It just means we’re still too lazy to study it properly. The FDA’s too slow. Pharma’s too greedy. And we’re the guinea pigs.

Zabihullah Saleh

January 2, 2026 AT 04:52In Afghanistan, we used to say: ‘The best medicine is the one you don’t need.’ Back then, we didn’t have pills - we had lentils, exercise, and prayer. Now we have Januvia and panic. Maybe we lost something in the translation. Not every problem needs a pill. But if you need one? At least know what you’re signing up for.

Rick Kimberly

January 4, 2026 AT 00:04While the relative risk increase of acute pancreatitis associated with DPP-4 inhibitors has been statistically significant in multiple meta-analyses, the absolute risk remains low. Clinical decision-making must weigh this against the favorable metabolic profile and cardiovascular safety data. It remains a reasonable option in select patient populations, particularly those with contraindications to other agents.

Terry Free

January 5, 2026 AT 12:33Oh wow. A drug that doesn’t make you gain weight? Shocking. And it doesn’t cause hypoglycemia? Revolutionary. Guess what? So does not eating sugar. But no one gets paid to tell you that. So they sell you a pill that might turn your pancreas into a warzone. Congrats, you’re a walking ad for Big Pharma.

Lindsay Hensel

January 5, 2026 AT 13:38This is precisely why shared decision-making matters. We owe our patients transparency - not fear, not hype, but clarity. If a patient values convenience and weight neutrality, and has no history of pancreatitis or gallstones, a DPP-4 inhibitor may still be appropriate. But only after a thorough, calm, and documented discussion.

Sophie Stallkind

January 6, 2026 AT 12:43Thank you for this comprehensive and well-referenced overview. It is imperative that clinicians and patients alike remain informed about both the benefits and potential adverse effects of pharmacologic interventions. This post exemplifies the kind of balanced, evidence-based communication that is too often absent in public discourse.