When you take a medication like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin, even a tiny change in dose can mean the difference between healing and harm. These are NTI drugs - narrow therapeutic index drugs - and they demand far more than just a generic label to be safe. The FDA doesn’t treat them like regular generics. There are special rules, tighter limits, and complex testing that most people never hear about. If you or someone you care for relies on one of these drugs, understanding how the FDA ensures safety isn’t just helpful - it’s essential.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

| Criteria | Threshold |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic index | ≤ 3 |

| Minimum effective to minimum toxic dose ratio | ≤ 2-fold |

| Therapeutic monitoring required | Yes |

| Within-subject variability | ≤ 30% |

| Dose adjustments | Often <20% |

Not every potent drug is an NTI drug. The FDA uses five specific criteria to decide. The most important? A therapeutic index of 3 or less. That means the gap between the dose that works and the dose that causes harm is dangerously small. For example, digoxin - used for heart rhythm issues - has a therapeutic index of about 2. A little too much, and you risk fatal arrhythmias. A little too little, and the heart condition worsens.

Other signs include the need for regular blood tests to monitor levels, tiny dose changes (like 0.125 mg increments), and low variability in how the body handles the drug from day to day. Drugs like carbamazepine, valproic acid, lithium, and tacrolimus all meet these standards. The FDA doesn’t publish a single public list. Instead, they define NTI status case by case in product-specific guidance documents. If a generic version is approved, you’ll find the exact bioequivalence rules listed there.

Why Standard Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

For most generic drugs, the FDA accepts a 80% to 125% range for bioequivalence. That means the generic can deliver between 80% and 125% of the brand’s active ingredient. For a blood pressure pill, that’s usually fine. For an NTI drug? That’s a 45% swing in exposure - a huge risk.

Imagine you’re on warfarin. Your doctor carefully adjusts your dose so your INR stays at 2.5. You switch to a generic. If that generic delivers 120% of the original drug’s concentration, your INR could spike to 4.5 - putting you at risk of a brain bleed. That’s why the FDA tightened the rules.

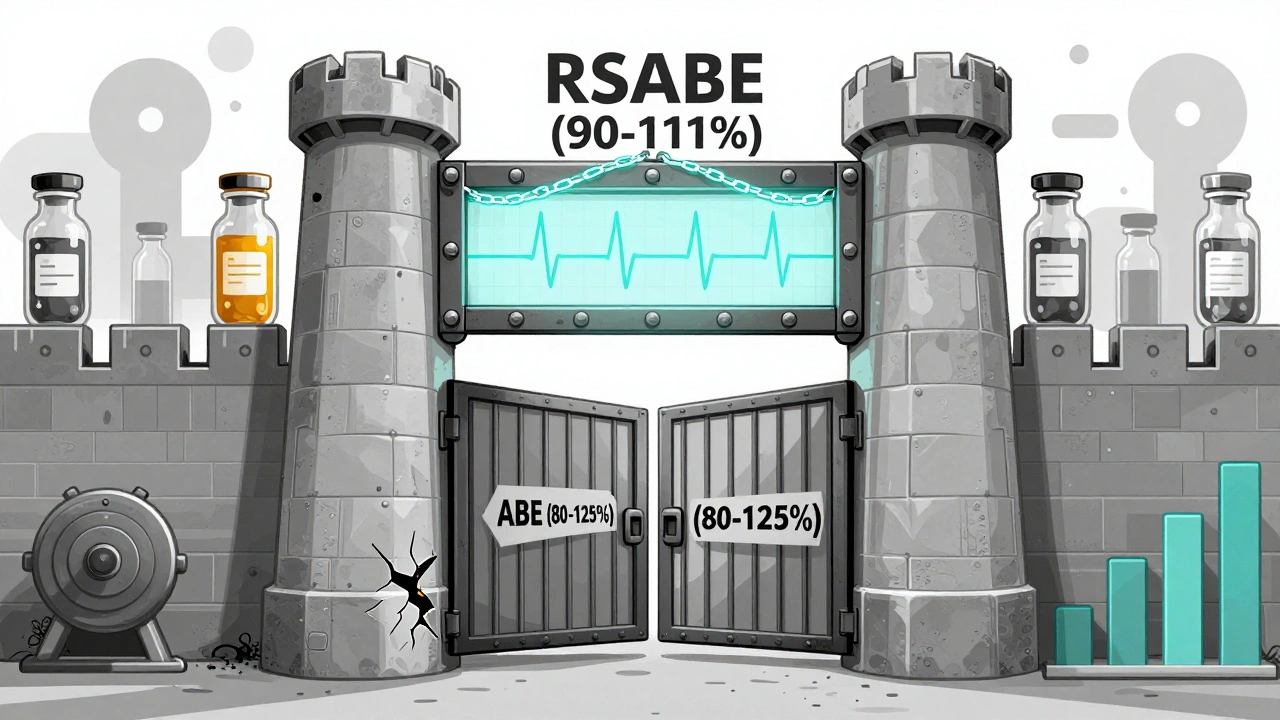

In 2010, the Advisory Committee for Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Pharmacology voted 11-2 that the old 80-125% rule was unsafe for NTI drugs. They recommended a new standard: 90% to 111%. That’s a much smaller window. It’s not just a tweak. It’s a complete overhaul.

The FDA’s Dual-Approval System for NTI Drugs

The FDA doesn’t just use one test. It uses two - and you have to pass both.

- Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE): This method adjusts the acceptable range based on how variable the brand-name drug is in the body. If the brand varies a lot between doses, the generic can vary a bit more too - but only up to a point.

- Conventional Average Bioequivalence (ABE): Even if the RSABE test passes, the generic must still meet the 80-125% range. This acts as a safety net.

There’s also a third layer: variability comparison. The FDA checks if the generic’s blood concentration varies more than the brand’s. The upper limit of the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of within-subject standard deviation (test/reference) must be ≤ 2.5. That means the generic can’t be more unpredictable than the brand.

And quality control? It’s stricter too. For non-NTI drugs, the active ingredient can vary between 90% and 110%. For NTI drugs, that range shrinks to 95% to 105%. One extra milligram in a tablet could push a patient over the edge. That’s why the FDA demands tighter manufacturing control.

Real-World Examples: Tacrolimus, Warfarin, and Phenytoin

Tacrolimus, used after organ transplants, is a textbook NTI drug. Studies show that two different generic versions - both approved under FDA’s 90-111% rule - can still behave differently in patients. One might cause rejection; another might cause kidney damage. That’s why transplant centers often stick with the brand or use only one generic supplier.

Warfarin is another. Even with strict testing, some patients report changes in INR after switching generics. The FDA says this is rare and usually due to other factors - diet, other meds, illness. But real-world data shows that clinicians remain cautious. Many still avoid switching unless absolutely necessary.

Phenytoin, an antiseizure drug, has a long history of controversy. Multiple studies found that different generics, even if FDA-approved, led to breakthrough seizures in some patients. The FDA acknowledges this concern. But they also point to large-scale studies showing that, overall, generic NTI drugs perform safely in the real world - when used correctly.

Why Some Doctors Still Hesitate

Despite FDA approval, many neurologists, cardiologists, and transplant specialists don’t automatically substitute NTI generics. Why?

- Conflicting data: Some small studies show differences; others don’t. It’s hard to reconcile.

- Patient anxiety: Patients who’ve been stable on a brand for years don’t want to risk a seizure or rejection.

- State laws: In some states, pharmacists must get patient consent before switching an NTI drug. Others ban substitution entirely.

- Pharmacist training: Not all pharmacists know the difference between standard and NTI bioequivalence rules.

The FDA’s position is clear: approved generics are therapeutically equivalent. But they also admit that education is lacking. They’ve called for better training for pharmacists - especially those in community settings - and for clearer communication with patients.

What This Means for You

If you take an NTI drug, here’s what you should do:

- Know your drug: Is it on the list? Common ones include digoxin, lithium, carbamazepine, valproic acid, everolimus, and cyclosporine.

- Don’t switch without talking to your doctor: Even if your pharmacy says it’s the same, ask if the generic is approved under NTI standards. Not all generics are created equal.

- Monitor closely: If you do switch, ask for a blood test within 2-4 weeks. Your levels may shift.

- Ask about the manufacturer: Some generics come from the same factory as the brand. Others don’t. Ask your pharmacist which one you’re getting.

- Keep a record: Write down the name of your drug - brand or generic - and the manufacturer. If something changes, you’ll know exactly what to report.

The FDA’s system is designed to protect you. But it’s not perfect. It relies on rigorous testing, but it can’t predict every patient’s reaction. Your awareness is the final layer of safety.

What’s Next for NTI Drugs?

The FDA is working to make NTI classification more objective. In 2022, they moved from vague descriptions to a hard cutoff: therapeutic index ≤ 3. That’s a big step toward consistency.

They’re also pushing for global alignment. Right now, Europe and Canada use simpler rules - just tighten the bioequivalence range. The U.S. uses a more complex, variability-based approach. Harmonizing these methods could make it easier for manufacturers and safer for patients worldwide.

Meanwhile, more generic NTI drugs are hitting the market. About 15% of new generic approvals in 2022 involved NTI drugs. That means more options - but also more responsibility on the part of patients and providers to get it right.

Are all generic NTI drugs the same?

No. Even if two generics are FDA-approved under NTI standards, they can still behave differently in your body. The FDA’s testing ensures safety, but individual responses vary. Stick with one manufacturer if you’re stable. Don’t switch unless your doctor approves.

Can I switch from brand to generic for my NTI drug?

Yes - but only with your doctor’s approval. The FDA says approved generics are safe and effective. But because small changes can matter, your doctor should monitor your condition after the switch, especially with drugs like warfarin or phenytoin. Never switch on your own.

Why does the FDA use a 90-111% range instead of 80-125%?

Because for NTI drugs, a 20% difference in blood concentration can cause serious harm. The 80-125% range is too wide. The 90-111% range reduces that risk by limiting exposure variation to just 21% instead of 45%. It’s based on pharmacometric data showing this range matches clinical safety.

How do I know if my drug is an NTI drug?

Check the FDA’s product-specific guidance documents or ask your pharmacist. Common NTI drugs include digoxin, lithium, phenytoin, warfarin, carbamazepine, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. If your doctor orders regular blood tests to adjust your dose, your drug is likely an NTI drug.

Do state laws affect NTI drug substitution?

Yes. Some states require pharmacist notification, patient consent, or even prohibit automatic substitution for NTI drugs. Others allow it. Check your state’s pharmacy board rules. Even if the FDA approves substitution, your state may have extra protections.

Audrey Crothers

December 12, 2025 AT 02:04Just switched my mom from brand to generic warfarin last month. She’s been stable for 20 years, but I was terrified. We did the blood test after 3 weeks-INR was perfect. 😌 FDA’s rules actually saved us. Don’t panic, but DO ask your pharmacist which maker it is.

Stacy Foster

December 13, 2025 AT 22:51They’re lying. The FDA doesn’t care about you. Big Pharma owns them. That 90-111% range? A gimmick. I’ve seen patients crash after switching. They bury the data. The real reason they allow generics? To save a buck. Your life is a spreadsheet.

Reshma Sinha

December 14, 2025 AT 06:08As a clinical pharmacist in Mumbai, I can confirm: NTI drugs demand precision. The RSABE framework is brilliant-especially the within-subject variability cap at 2.5. But here’s the kicker: in low-resource settings, even brand-name drugs have bioavailability issues. We need global standardization, not just FDA tweaks. Let’s align with WHO guidelines too!

Lawrence Armstrong

December 15, 2025 AT 01:15My dad’s on tacrolimus post-kidney transplant. We stick with the brand. No exceptions. 🤝 The FDA says generics are fine, but I’ve seen too many stories where one batch was fine and the next wasn’t. Better safe than sorry. Also, check the lot number. Seriously.

Donna Anderson

December 16, 2025 AT 02:05OMG I just found out my phenytoin is generic and I didn’t even know! I’ve been fine for 5 years but now I’m paranoid 😭 I’m calling my neurologist tomorrow. Why is this so hard to find out?? Pharmacy never told me.

Levi Cooper

December 17, 2025 AT 15:42Why does America need such complicated rules? In Europe, they just use 90-110% and call it a day. We’re over-engineering because we’re scared of lawsuits. Other countries handle this fine. Maybe we should stop treating every patient like a liability.

nikki yamashita

December 19, 2025 AT 05:31Just read this and cried. My sister’s on lithium. We always use the same generic. Never switch. Period. You’re not just taking a pill-you’re trusting a system. Stay informed. Stay safe. 💪

Rob Purvis

December 20, 2025 AT 13:45Important note: The FDA’s 90-111% range isn’t arbitrary-it’s derived from pharmacometric modeling of over 12,000 patient data points across 17 studies. The 80-125% range? That’s for non-NTI drugs, where a 45% swing is clinically negligible. But for drugs like digoxin? A 10% shift can trigger toxicity. The dual-testing system (RSABE + ABE) is the gold standard because it accounts for both average exposure AND variability. If your doctor says "it’s all the same," they’re misinformed.

Laura Weemering

December 21, 2025 AT 15:27...but what if the system is designed to fail us? Who really benefits from this complexity? The pharmaceutical corporations? The regulators who get paid to approve? We’re told to trust, but no one ever explains why the same drug, made in the same factory, behaves differently across batches... and no one is held accountable when people die because of a 5% variance in absorption. We’re just supposed to be grateful for the "safety net"? I’m not convinced.