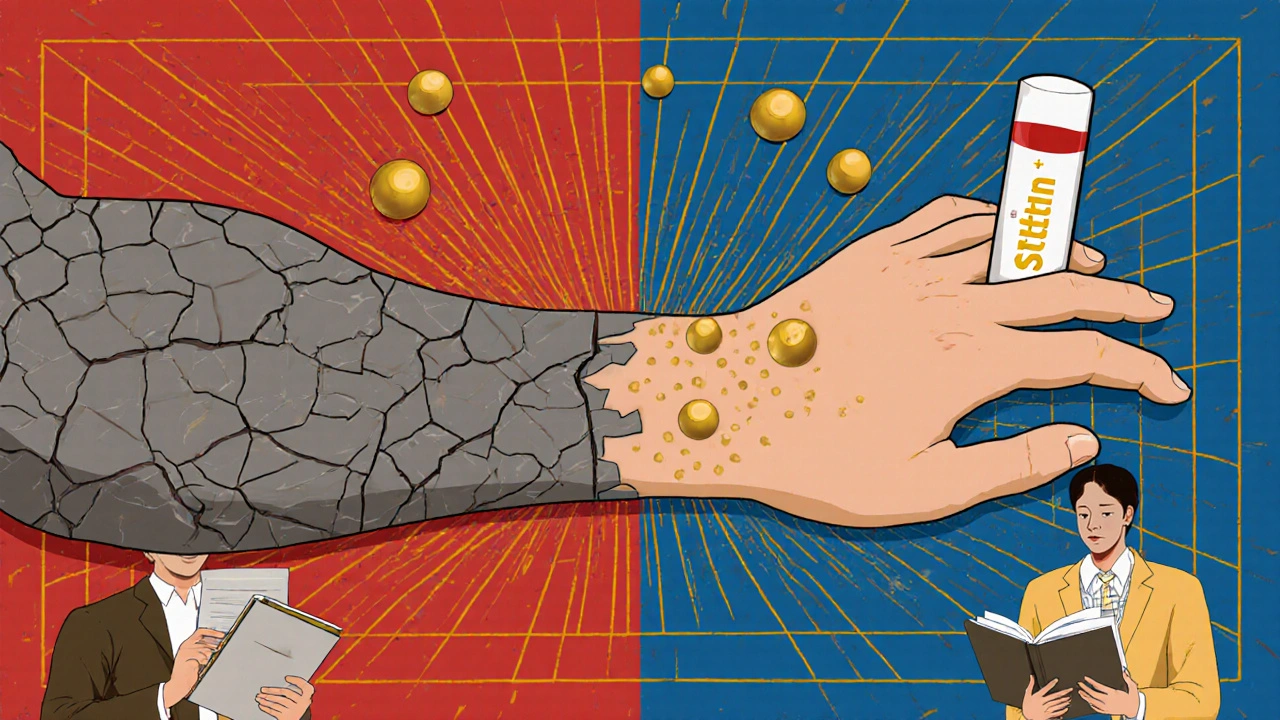

Psoriasis isn’t just a rash. For many people, it’s a constant battle-flaking skin, burning, itching, and the emotional toll that comes with it. When topical creams and light therapy don’t cut it, doctors turn to oral medications like acitretin. But how does a drug originally developed for acne end up being one of the most powerful tools against severe psoriasis? The answer lies in how it rewires the life cycle of skin cells.

What Acitretin Actually Does to Skin Cells

Acitretin is a synthetic version of vitamin A, part of a class of drugs called retinoids. It doesn’t kill skin cells or suppress the immune system like some other psoriasis treatments. Instead, it tells your skin to slow down.

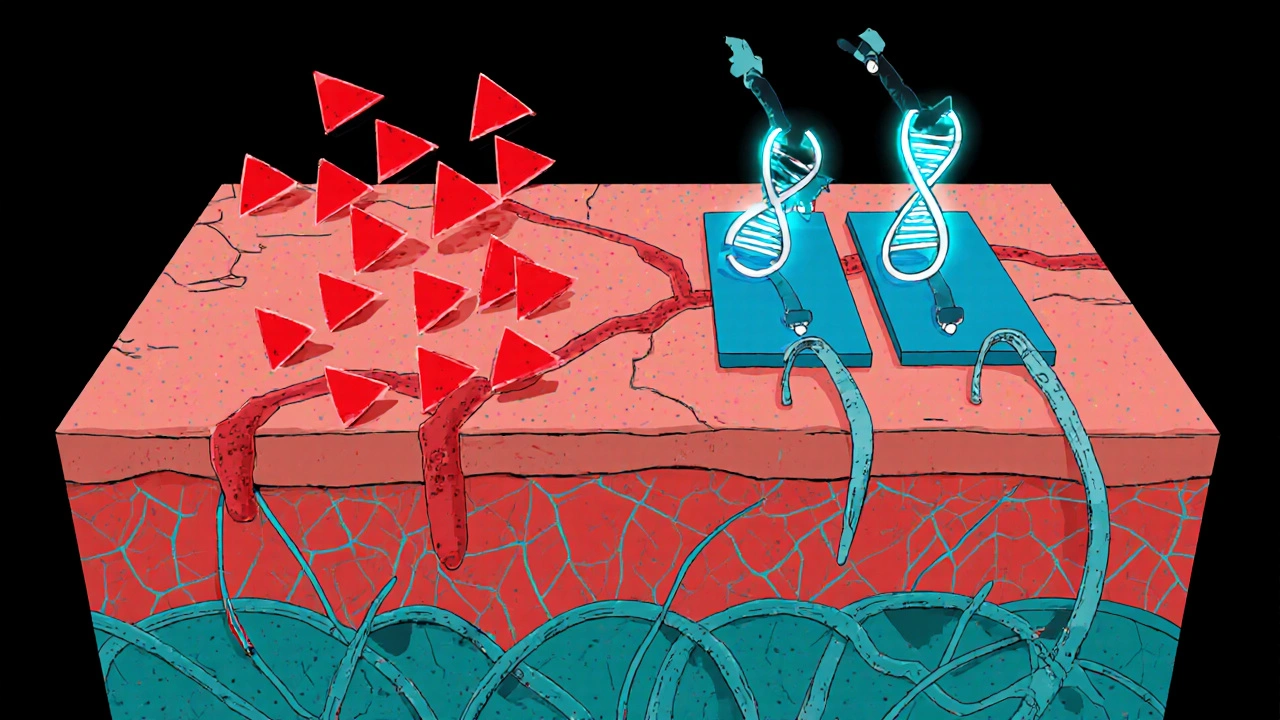

In healthy skin, cells are born in the deepest layer, slowly rise to the surface over about 28 days, and then flake off. In psoriasis, that process speeds up to just 3 to 7 days. The result? Skin cells pile up before they’re ready, forming thick, scaly plaques.

Acitretin binds to special receptors in skin cells called retinoic acid receptors (RARs). Once bound, it changes how genes are turned on and off. Specifically, it reduces the activity of genes that drive rapid cell division and increases genes that help cells mature properly. The outcome? Skin cells take longer to reach the surface, and when they do, they’re more like normal cells-less inflamed, less sticky, less likely to clump.

Why It Works Best for Plaque Psoriasis

Not all types of psoriasis respond the same way to acitretin. It’s most effective for plaque psoriasis-the most common form, affecting about 80% of people with the condition. That’s because plaque psoriasis is driven by excessive skin cell production, which is exactly what acitretin targets.

Studies from the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology show that after 12 to 16 weeks of treatment, nearly 60% of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis saw at least a 75% improvement in their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores. That’s a major drop in scaling, redness, and thickness.

It’s less effective for pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis, where immune system overdrive plays a bigger role than just fast cell turnover. That’s why doctors often pair acitretin with other treatments-like methotrexate or biologics-to cover more angles.

How Long Does It Take to Work?

Unlike steroids that calm redness overnight, acitretin doesn’t give quick fixes. Most people start noticing changes after 4 to 6 weeks. But the real results show up after 12 weeks. That’s why sticking with it matters-even when your skin still looks bad after a month.

One patient from Toronto, a 42-year-old teacher with a 12-year history of psoriasis, told her dermatologist she was ready to quit after 8 weeks. She restarted the treatment the next day. By week 16, her nails were growing normally again, and the plaques on her elbows had vanished. She’s been on a low maintenance dose for two years now.

Patience is part of the treatment. Acitretin isn’t a cure, but it can turn a daily struggle into something manageable.

The Side Effects You Can’t Ignore

Acitretin isn’t gentle. Because it affects how cells grow everywhere-not just in the skin-it comes with a list of side effects.

- Dry skin, lips, and eyes-almost everyone gets this. Lip balm and artificial tears aren’t optional.

- Increased sun sensitivity. You need to wear SPF 50+ every day, even in winter.

- Hair thinning or loss. It’s usually temporary, but it can be distressing.

- Elevated triglycerides and liver enzymes. Blood tests every 2 to 3 months are required.

- Headaches and muscle aches. These are common in the first few weeks.

The biggest risk? Birth defects. Acitretin stays in your body for years-even after you stop taking it. That’s why women of childbearing age must use two forms of birth control for at least three years after the last dose. Men don’t need to worry about passing it to a partner, but they should avoid fathering a child during treatment and for at least three months after stopping.

It’s not for everyone. If you have liver disease, high triglycerides, or are pregnant, acitretin is off the table. Your doctor will check your liver function and lipid levels before and during treatment.

How It Compares to Other Oral Psoriasis Drugs

There are three main oral options for moderate to severe psoriasis: acitretin, methotrexate, and apremilast. Here’s how they stack up.

| Drug | How It Works | Time to Results | Key Risks | Monitoring Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acitretin | Slows skin cell growth | 8-16 weeks | Dryness, high triglycerides, birth defects | Liver enzymes, lipids every 2-3 months |

| Methotrexate | Suppresses immune system | 4-8 weeks | Liver damage, low blood counts | Blood tests monthly |

| Apremilast | Reduces inflammatory signals | 8-12 weeks | Nausea, diarrhea, weight loss | Weight and mood checks |

Acitretin stands out because it doesn’t weaken your immune system. That makes it a good option for people who get frequent infections or don’t want to risk serious side effects like tuberculosis reactivation, which can happen with methotrexate or biologics.

But it’s not as strong as biologics for very severe cases. And unlike apremilast, it doesn’t help with psoriatic arthritis. So if joint pain is part of your psoriasis, you’ll likely need something else too.

Combining Acitretin with Other Treatments

Many dermatologists use acitretin as a backbone-not a solo act. When paired with UVB phototherapy, results improve faster and the dose of acitretin can be lowered, reducing side effects. This combo is called Re-PUVA when used with psoralen and UVA, but UVB is safer and more common now.

Another common combo is acitretin with methotrexate. Studies show this duo clears skin better than either drug alone, and allows lower doses of both. That means fewer side effects over time.

It’s also used as a bridge. Some patients start with acitretin to get their psoriasis under control, then switch to a biologic for long-term maintenance. That way, they avoid years of daily pills and the risk of liver damage from methotrexate.

What Happens When You Stop Taking It?

Psoriasis doesn’t disappear just because you stop acitretin. In fact, many people see a flare-up within 2 to 6 months after stopping. That’s why some stay on low doses long-term-like 10 to 25 mg per day-just to keep symptoms in check.

But long-term use isn’t risk-free. The longer you’re on it, the higher the chance of bone changes or liver issues. That’s why regular monitoring is non-negotiable. Your doctor won’t just check your blood-they’ll also ask about joint pain, vision changes, and how your skin feels.

There’s no magic way to prevent rebound. But if you stop and flare up, restarting acitretin often works again. It’s not like your body becomes resistant. It just needs time to relearn how to slow down skin growth.

Real-Life Tips for Taking Acitretin Successfully

If you’re prescribed acitretin, here’s what actually helps in daily life:

- Take it with food-especially fatty meals. It absorbs much better that way.

- Keep lip balm in every bag, car, and desk drawer. Your lips will crack without it.

- Use a humidifier at night. Dry air makes skin worse.

- Wear gloves when washing dishes or cleaning. Soaps and cleaners dry out skin faster.

- Don’t drink alcohol. It turns acitretin into a more dangerous form in your body.

- Track your symptoms in a journal. Note when your skin improves or worsens. That helps your doctor adjust your dose.

One patient in Hamilton started a simple habit: every morning, he applied moisturizer before getting dressed. Within a month, his flaking dropped by half. Small steps add up.

Is Acitretin Right for You?

Acitretin isn’t a first-line treatment. It’s for people with moderate to severe psoriasis who haven’t responded to creams, light therapy, or safer oral drugs. It’s also an option if biologics aren’t covered by insurance or are too expensive.

If you’re tired of daily creams, hate injections, and want something that doesn’t shut down your immune system, acitretin might be worth a try. But it demands discipline-blood tests, sun protection, birth control, and patience.

It’s not a miracle. But for thousands of people, it’s the difference between hiding their skin and living without shame.

How long does acitretin stay in your body?

Acitretin has a long half-life. It can stay in your system for up to three years after you stop taking it. That’s why women must avoid pregnancy for at least three years after the last dose. The drug can be stored in fat tissue and slowly released, which is why alcohol use after stopping is dangerous-it can convert acitretin back into an active form.

Can acitretin cure psoriasis?

No, acitretin doesn’t cure psoriasis. It controls the symptoms by slowing down skin cell production. Once you stop taking it, psoriasis usually returns. But many people use it long-term at low doses to keep flare-ups under control.

Does acitretin cause weight gain?

No, acitretin doesn’t cause weight gain. In fact, some people lose a small amount of weight due to appetite changes or gastrointestinal side effects. This is different from biologics or corticosteroids, which can lead to weight gain.

Can I take acitretin if I have high cholesterol?

It depends. Acitretin can raise triglycerides and cholesterol levels. If your levels are already high, your doctor may avoid it or start you on a low dose with frequent blood tests. Some patients need to take statins alongside acitretin to manage lipid levels.

Is acitretin safe for older adults?

Yes, but with caution. Older adults are more sensitive to side effects like dry skin and bone changes. Doctors usually start with lower doses-10 to 25 mg per day-and monitor liver and kidney function more closely. It’s still used in people over 65 if benefits outweigh risks.

If you’re considering acitretin, talk to your dermatologist about your goals, your lifestyle, and your long-term health. It’s not the easiest drug to take-but for the right person, it can be life-changing.

Sherri Naslund

November 19, 2025 AT 11:57so acitretin is just vitamin a but like… fancy and expensive? i mean i eat carrots every day and my skin is fine??? why do i need a pill that turns my lips into cracked desert sand???

Ashley Miller

November 20, 2025 AT 22:04lol of course they don’t tell you the real reason they push this drug. Big Pharma knows if you’re taking acitretin, you can’t drink alcohol. So they’re secretly trying to kill the beer industry. Also, the ‘3-year pregnancy ban’? That’s just to keep women docile. I heard they’re testing it on rats and the babies come out with extra eyes. Not joking. Google it.

Martin Rodrigue

November 22, 2025 AT 02:34While the article provides a reasonably accurate overview of acitretin’s pharmacodynamics, it omits critical discussion regarding the metabolic pathway of acitretin’s conversion to etretinate, which possesses a significantly longer half-life. The clinical implications of this metabolic interconversion are not adequately addressed, particularly in populations with impaired hepatic function. Furthermore, the assertion that acitretin does not suppress the immune system is misleading; while it does not directly target lymphocytes, downstream modulation of cytokine expression via RAR-beta binding does exert indirect immunomodulatory effects.

william volcoff

November 22, 2025 AT 09:22My dermatologist put me on this after 8 years of topical hell. First month? Dry as a bone. Lips split open like a Thanksgiving turkey. But by week 12? My elbows looked like normal skin. No more hiding sleeves in summer. I still use SPF 50 every single day-even in December. And yeah, I keep lip balm in my car, my purse, my pocket, my damn sock drawer. Worth it.

Freddy Lopez

November 22, 2025 AT 22:57It’s fascinating how a molecule derived from a vitamin essential to vision and epithelial integrity can be repurposed to recalibrate a pathological cellular cycle. The elegance lies not in destruction, but in restoration-the body’s own mechanisms, gently guided. Psoriasis isn’t an enemy to be eradicated, but a miscommunication within the skin’s ecosystem. Acitretin doesn’t silence it; it teaches it to listen again.

Brad Samuels

November 23, 2025 AT 01:10I know someone who took this and lost all their hair. It scared them so bad they quit. But then they restarted after a year, and now their skin’s better than ever. I just want people to know: it’s rough at first, but it’s not forever. And if you’re struggling, you’re not alone. Talk to your doc. Keep going. Even if it feels like your skin hates you right now.

Mary Follero

November 24, 2025 AT 06:49Just want to add: take it with a fatty meal. Like, actually eat bacon or avocado with it. I forgot once and thought it wasn’t working-turns out my body just wasn’t absorbing it. Also, humidifier + coconut oil on skin at night = game changer. And no, alcohol doesn’t just ‘make it worse’-it can reactivate the drug like a ghost in your system. I didn’t know that until my cousin had a flare after a wedding toast. Don’t be like her.

Will Phillips

November 25, 2025 AT 14:27They say it’s safe but they’re lying. I saw a guy on Reddit who took it and his liver exploded. He was 29. They don’t tell you about the bone density loss either. And why do they say men don’t need to worry? What if the sperm is contaminated? They don’t test that. And why is it banned in Europe? Oh right-because they’re smarter there. You’re being used as a guinea pig. Stop now. Just stop.

Arun Mohan

November 27, 2025 AT 05:21Interesting how you all treat this like some miracle cure. I mean, in India we’ve had ayurvedic protocols for psoriasis for millennia-turmeric, neem, panchakarma. But no, you’d rather ingest a synthetic retinoid that costs $800 a month and turns your skin into sandpaper. How colonial. How pathetic. You think science is progress? This is just capitalism repackaging suffering as treatment.