TZD Heart Failure Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment

Answer these questions to determine your risk of fluid retention from thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing dangerous side effects is critical. Thiazolidinediones - like pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia) - were once popular for their ability to make the body more sensitive to insulin. But for many patients, especially those with heart problems, these drugs come with a hidden risk: fluid retention that can lead to heart failure.

How Thiazolidinediones Work - and Why They Cause Swelling

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) activate a protein called PPAR-γ, which helps fat and muscle cells respond better to insulin. That’s why they’re effective at lowering blood sugar. But PPAR-γ isn’t just in fat and muscle. It’s also in the kidneys, blood vessels, and heart. When TZDs turn on this protein in the kidneys, they trigger sodium and water retention. This isn’t just a minor side effect - it’s a measurable change in your body’s fluid balance.

Studies show TZDs increase blood volume by 6-7% in healthy people. That extra fluid doesn’t just disappear. It collects in the legs, ankles, and feet - what doctors call peripheral edema. About 7% of people taking TZDs alone develop this swelling. When combined with insulin, that number jumps to 15%. In some cases, the fluid moves into the lungs, causing pulmonary edema - a serious condition that mimics heart failure.

The Link Between Fluid Retention and Heart Failure

It’s not that TZDs directly damage the heart. Instead, they overload it with fluid. If your heart is already weak - from prior heart attacks, high blood pressure, or aging - that extra volume can push it past its limit. The heart can’t pump efficiently, pressure builds up in the lungs, and symptoms like shortness of breath, fatigue, and swelling get worse.

A 2018 analysis of over 424,000 U.S. adults with diabetes found that 40.3% of those taking TZDs already had signs of heart failure: a diagnosis of heart failure, low heart pumping ability (ejection fraction under 40%), or were on loop diuretics. That’s nearly half of all TZD users - despite guidelines clearly saying these drugs shouldn’t be used in people with heart failure.

In one study of 111 diabetic patients with existing heart failure, 17% developed new or worsening fluid retention after starting a TZD. Six of them had visible signs of heart strain, like swollen neck veins. Two developed full-blown pulmonary edema. The risk didn’t depend on how bad their heart failure was - it depended on whether they were on insulin or were women.

Who Should Avoid Thiazolidinediones?

The FDA and major medical groups have clear rules:

- Do NOT use TZDs in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III or IV heart failure - that’s moderate to severe heart failure with symptoms even at rest.

- Avoid them in anyone with a history of heart failure, even if it’s stable.

- Use extreme caution in patients over 65, those with kidney disease, or those already taking insulin.

- Women are at higher risk for fluid retention - more than men - even without existing heart disease.

Despite these warnings, many patients still get prescribed TZDs. Why? Because they work well. Unlike some other diabetes drugs, TZDs rarely cause low blood sugar. They also improve fat metabolism and may reduce artery plaque buildup. But these benefits don’t outweigh the risks for most people with heart issues.

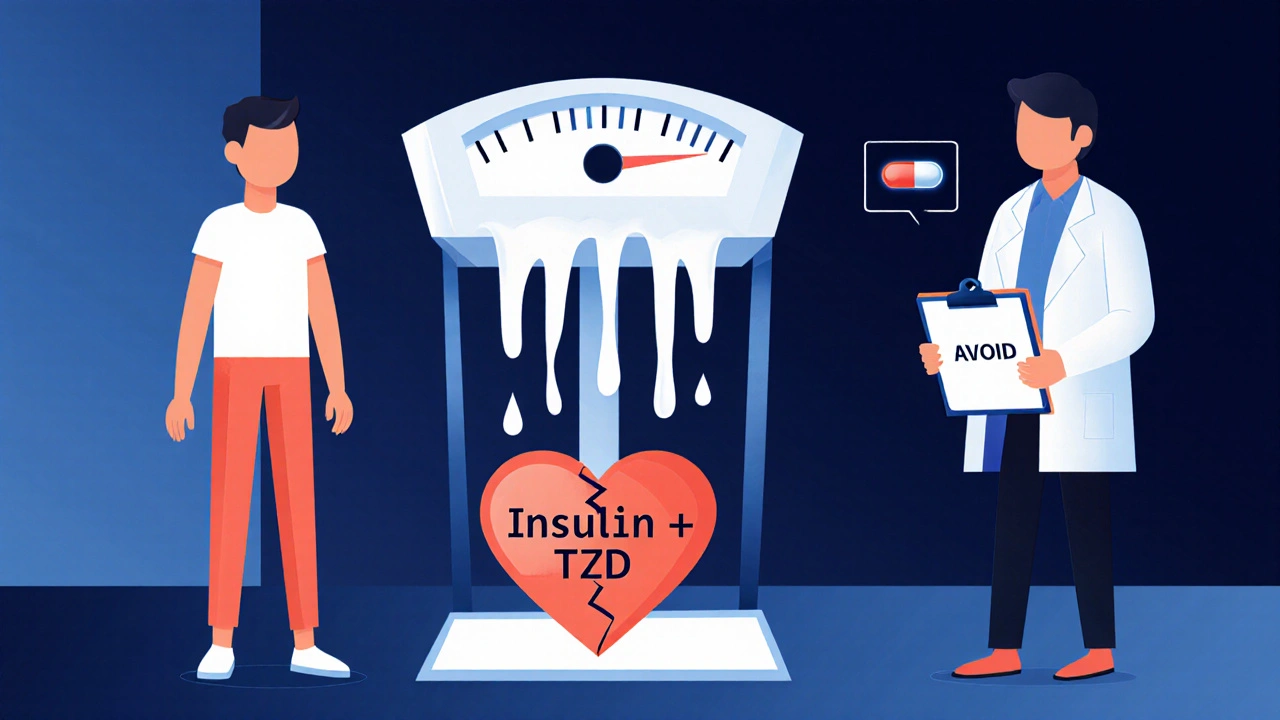

What Happens When You Take TZDs With Insulin?

The combination is especially dangerous. Insulin itself causes the kidneys to hold onto sodium. TZDs do the same. Together, they create a perfect storm for fluid overload.

Studies show that when TZDs are added to insulin therapy, the chance of developing swelling jumps from 5% to 15%. Weight gain of 10 pounds or more is common. Patients often don’t notice the swelling until their ankles are puffy or their rings won’t fit. By then, fluid may already be in the lungs.

Doctors sometimes try to manage this with diuretics - water pills like furosemide. But TZD-induced fluid retention is often resistant to these drugs. The only reliable fix? Stopping the TZD. Once the drug is out of the system, the swelling usually goes down within days to weeks.

Current Guidelines and Real-World Use

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Heart Association (AHA) agree: TZDs should be avoided in patients with heart failure. The 2022 ADA Standards of Care say they can be considered only in patients with Class I or II heart failure - mild symptoms during activity - and only if closely monitored.

But real-world practice doesn’t always match the guidelines. The 2018 Circulation study found that nearly half of TZD users had clear signs of heart failure - even though they weren’t supposed to be taking the drug. That suggests many providers either don’t know the guidelines, or they underestimate the risk.

Meanwhile, pioglitazone is still widely available, costing around $300 for a 30-day supply of 30mg tablets. Rosiglitazone is harder to get - it’s only available through a restricted program because of past concerns about heart attacks. But both drugs carry the same fluid retention risk.

What to Do If You’re on a TZD

If you’re taking pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, here’s what you need to do:

- Check for swelling in your ankles, feet, or abdomen. If you’ve gained more than 5 pounds in a week, call your doctor.

- Watch for shortness of breath - especially when lying down or during light activity.

- Ask your doctor if you have any signs of heart failure: low ejection fraction, history of heart attack, or use of diuretics.

- If you’re on insulin, ask if the TZD is still necessary. The combination increases risk significantly.

- Don’t stop the drug on your own. Talk to your provider about safer alternatives like GLP-1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors, which actually protect the heart.

Many patients are surprised to learn that newer diabetes drugs - like semaglutide (Ozempic) or empagliflozin (Jardiance) - don’t just lower blood sugar. They reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization and death. For most people with diabetes and heart disease, these are better options than TZDs.

Why This Risk Is Still Under-Recognized

One reason TZDs are still prescribed is that fluid retention doesn’t always look like heart failure. It starts as mild swelling. Patients think it’s just aging or sitting too long. Doctors may mistake it for a side effect of another drug. And because the drugs work so well for blood sugar, it’s easy to overlook the warning signs.

But the data is clear: TZDs are not safe for patients with heart failure. Even in those without a diagnosis, they can trigger it. The risk isn’t rare - it’s common enough that nearly one in five users develops new fluid overload.

The bottom line? TZDs have a place in diabetes care - but only for a small group of patients with no heart disease, no kidney problems, and no insulin use. For everyone else, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Can thiazolidinediones cause heart failure in people without prior heart disease?

Yes. While TZDs are most dangerous in people with existing heart problems, they can trigger fluid retention and heart failure in people with no prior diagnosis. Studies show that even healthy individuals experience a 6-7% increase in blood volume after starting TZDs. In susceptible people - especially women, older adults, or those on insulin - this extra fluid can overwhelm the heart and lead to symptoms of heart failure.

Are there safer alternatives to thiazolidinediones for type 2 diabetes?

Yes. Drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide, liraglutide) are now preferred for people with diabetes and heart disease. These medications lower blood sugar without causing fluid retention - and in fact, they reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization and death. They’re often more effective and safer than TZDs, especially for older adults or those with kidney or heart issues.

Why do TZDs cause fluid retention?

TZDs activate PPAR-γ receptors in the kidneys, which increases sodium and water reabsorption. This leads to higher blood volume. The exact mechanism isn’t fully understood, but it likely involves increased activity of sodium transporters in the kidney’s collecting duct and possibly the proximal tubule. This is different from how most diuretics work, which is why standard water pills often don’t help.

Is pioglitazone safer than rosiglitazone for the heart?

In terms of fluid retention and heart failure risk, both drugs are equally risky. Rosiglitazone was linked to a higher chance of heart attacks in early studies, leading to restrictions. Pioglitazone didn’t show the same heart attack risk, but both cause the same level of fluid retention. Neither is considered safe for people with heart failure.

How long does it take for fluid retention to go away after stopping a TZD?

Once you stop taking a TZD, fluid retention usually begins to improve within a few days. Most patients see noticeable reduction in swelling within one to two weeks. Full resolution of symptoms like shortness of breath or weight gain typically takes up to four weeks. It’s important to monitor weight and symptoms closely during this time.

Adam Phillips

October 29, 2025 AT 13:25People act like medicine is some kind of moral choice but it's just chemistry and biology

Drugs don't care about your intentions or your willpower

If your kidneys start hoarding sodium because a protein got turned on too hard that's not a failure of character

It's just physics

We treat diabetes like it's a spiritual test when it's really a leaky pipe

And we keep patching it with more pills instead of replacing the whole system

TZDs work but they're like using duct tape on a burst water main

Yeah it stops the spray for a bit

But the pipe is still broken

And eventually it's gonna flood everything

Stop glorifying bandaids as solutions

Just admit we're playing whack-a-mole with biology

matt tricarico

October 30, 2025 AT 22:14It's amusing how the medical establishment pivots so dramatically on these drugs

First they were miracle agents for insulin sensitivity

Now they're poison

The same mechanism that made them effective is now the reason they're banned

It's not science

It's fashion

One year PPAR-γ is the holy grail

Next year it's the devil's switch

And the patients? They're the ones stuck in the middle

With no real understanding of why they were ever prescribed this in the first place

Pharma doesn't care

They just want the next patent

Patrick Ezebube

October 31, 2025 AT 14:12Did you know the FDA approved TZDs while the same people were covering up opioid data?

Same people

Same playbook

They knew the fluid retention was dangerous

They just didn't want to admit it until the lawsuits started rolling in

Now they're pushing SGLT2 inhibitors like they're magic

But guess what

Those are made by the same companies

Same labs

Same lobbyists

It's all one big circus

They sell you the problem

Then sell you the cure

Then sell you the next cure

And you pay for every step

Kimberly Ford

November 2, 2025 AT 02:30If you're on a TZD and you've gained 5 pounds in a week or your ankles are puffy

Don't wait

Call your doctor today

This isn't something that gets better on its own

And if you're on insulin too

The risk is even higher

There are better options now

GLP-1s and SGLT2s don't just lower sugar

They actually protect your heart

You deserve a treatment that helps

Not one that slowly breaks you down

You're not alone in this

Many people have switched and felt better within weeks

It's okay to ask for something safer

jerry woo

November 2, 2025 AT 20:46TZDs are the pharmaceutical equivalent of a guy who shows up to a fire with a garden hose

He's got good intentions

He's got a flashy title

But he's just making the damn thing worse

And then when you point out the water's flooding the basement

He says

"But your house looked better before I got here!"

Meanwhile

The real firefighters are standing there with actual extinguishers

GLP-1s

SGLT2s

They don't just put out the fire

They fix the wiring that caused it

And they don't leave your socks soaked in the process

So why are we still talking about garden hoses?

Rachel Marco-Havens

November 4, 2025 AT 05:45Women are at higher risk for fluid retention with TZDs

That's not an accident

That's a failure of clinical research

For decades trials were dominated by male subjects

So we didn't see the gender difference until it was too late

Now we're playing catch up

But the damage is done

Thousands of women were prescribed these drugs without being warned

And now they're told to just "monitor" the swelling

As if that's enough

It's not

It's negligence dressed up as caution

And the system still won't admit it

Kathryn Conant

November 5, 2025 AT 03:08Listen

If you're on a TZD

And you're tired all the time

And your shoes don't fit anymore

And you're breathing funny when you lie down

STOP

Don't wait for your next appointment

Don't wait for your doctor to "figure it out"

Call them right now

Ask for a switch

Ask for empagliflozin

Ask for semaglutide

These aren't "experimental"

They're the new standard

And they're saving lives

You deserve that

Not a relic from the 2000s

j jon

November 6, 2025 AT 09:53I was on pioglitazone for two years

Never thought the swelling was a big deal

Thought it was just getting older

Then I got winded walking to the mailbox

Went to the doc

Turns out my ejection fraction was down to 38%

Stopped the drug

Three weeks later

My ankles looked normal

And I could climb stairs without gasping

Switched to Jardiance

Best decision I ever made

Don't ignore the signs

Jules Tompkins

November 8, 2025 AT 08:43So the drug that makes your blood sugar better

Also makes your ankles look like water balloons

And then your lungs fill up like a bathtub

And you're supposed to be okay with that

Because it's "effective"

What even is medicine anymore

It's like buying a car that gets 50 mpg

But every time you drive it

The tires explode

And the gas tank leaks oil

And the radio plays funeral music

And you're told

"But it's the only one that doesn't stall!"

Yeah

But why are we still buying it

Sabrina Bergas

November 9, 2025 AT 03:05Everyone's acting like SGLT2 inhibitors are some revolutionary breakthrough

But they're just the next profit engine

Same pharma

Same patent clock

Same hype cycle

TZDs were the old magic bullet

Now it's the SGLT2s

Next it'll be some GLP-1/GIP combo

And we'll all be told this one's "game changing"

But the truth

Is that we're just swapping one flawed tool for another

While the real issue

Is that we treat diabetes like a puzzle to solve

Not a chronic condition to manage

And we never fix the root

Melvin Thoede

November 10, 2025 AT 18:23I'm a nurse

And I've seen this a hundred times

Older patient

On insulin and pioglitazone

Swollen legs

Weight gain

Shortness of breath

They think it's just "part of aging"

Then they get admitted for heart failure

And we pull the TZD

And boom

They're walking out in two weeks

It's not magic

It's just removing the toxin

Why do we wait until they're in the ER to do it

Because we're too busy chasing HbA1c numbers

And not looking at the person

Suzanne Lucas

November 10, 2025 AT 21:25My mom got prescribed rosiglitazone

She gained 20 pounds in 4 months

Could barely walk

Then got hospitalized for pulmonary edema

Turns out she had undiagnosed heart disease

They didn't check

Just said "oh you're diabetic so this is normal"

She's fine now

Switched to Ozempic

Lost 15 pounds

Can hike again

But I'll never forgive how they almost killed her

Just because they liked the HbA1c drop

And didn't want to admit they were wrong

Ash Damle

November 12, 2025 AT 03:44Thanks for this

I've been on pioglitazone for five years

Never realized the swelling was from the drug

Thought I just needed to exercise more

Just read this

Called my doctor

Switching to Jardiance next week

Wish I'd known sooner

But I'm glad I know now

And I'm not mad

Just ready to move forward